If the past year has taught us anything, it is not to underestimate the imminence of change. Confined to our homes, concerned about the health of our loved ones, we have watched a crisis play out on the global stage – we have deeply felt every emotional overture, and have been exposed to the collective trauma of loss.

We have seen a shift in the way that people are thinking about work, as they move from an office to working from home; we have seen a need for a new approach to leadership, team work, and collaboration; and we have seen changes in the thinking about our use of technology. This pandemic has therefore represented a large shift in the way that each of us lives our day-to-day lives.

For some of us, this felt like the end of everything we knew – for others, it was just the beginning.

As the pandemic has progressed, we have begun to learn more about the underlying factors that have caused some to be worse affected than others[1]. As part of this, clear links are beginning to be drawn between the health crisis and the other big crisis of our time: climate change[2].

Over the past few months, however, another crisis has become evident: a crisis of racism. Many of us watched with horror as the murder of George Floyd played out on our phone and computer screens – another trauma, another avoidable and tragic loss.

As breath became air, a match sparked and collective grief ignited in the form of the Black Lives Matter movement – a movement originally forged in the American crucible that emerged following the police murder of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile in 2016.

Moving across the stage, this fire has continued to spread, threatening the frail timber upon which our society is built.

Distinct though they may seem, these 3 crises can be drawn together by a single theme: inequality. Therefore, if we wish to halt the spread of the fire, we must begin to understand the role of inequality in all three of these crises. The time and space that the onset of COVID-19 has allowed may just be our opportunity to do this.

This pandemic may have completely changed how we live and interact, but it does not necessarily have to end in the negative: we have the opportunity to change and reflect, to build back better. We must take this end to what we thought we knew, and turn it into a beginning. We must begin to find ways to live more sustainably, to act more responsibly, and to take care of our human and non-human environment.

First, though, we need to take the time to reflect and understand just how we ended up here.

Three acts, one play

Act 1: A climate crisis

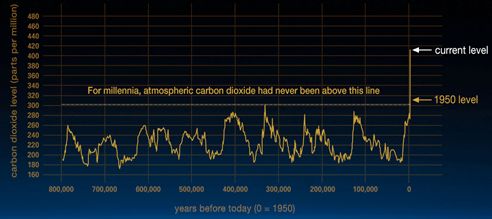

Climate change is a result of the build-up of anthropogenic greenhouse gases – primarily carbon dioxide (CO2) – in the atmosphere. The foothills of current global greenhouse gas concentrations were formed in the heat of industrialisation in the 1800s, with major contributions coming from the UK and the US. As CO2 plumed from factory chimneys, it formed the bedrock of the mountain of greenhouse gases that we now find ourselves under.

In Britain, it has been said that industrialisation was “carried through with exceptional violence”[3]. This violence was not, however, uncommon: enslavement of black and brown people has played a crucial role in the industrialisation of many nations[4]. In fact, Kathryn Yusuf goes as far to say that “[black] and brown death is the precondition of every Anthropocene origin story” [5], where the Anthropocene is the period of geological history in which the human’s influence on the environment can be discerned[6].

Thus, we find inequality at the centre of the climate crisis that we are currently facing. And, in fact, the trend for high income, industrialised nations to contribute more to climate change can still be seen today[7].

Act 2: A Racist Environment

Torn up by the exploitation of the many for the benefit of the few, the climate has been changed; and from uneven contribution comes global effect. The impacts of climate change will range from coral bleaching to the increasing frequency and severity of storms to the loss of large and diverse ecosystems. Beyond physical impacts, as with all crises, there will also be social impacts – in fact:

“People who are socially, economically, culturally, politically, institutionally, or otherwise marginalized are especially vulnerable to climate change […] This heightened vulnerability is rarely due to a single cause. Rather, it is the product of intersecting social processes that result in inequalities in socioeconomic status and income, as well as in exposure.”[8]

And so, the climate turns back on us – destroying the few, threating the many. Once again, however, the historically exploited and marginalised sit at the centre of the violence and destruction.

The plight of marginalised groups is already playing out across the globe, and has been for many years: one poignant example is the plight of Black communities in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina[9].

Act 3: A Health Crisis

Intersecting and amplifying, the two crises of climate change and racism have reached fever pitch as they play out in the context of the COVID-19 crisis.

Sitting in the toxin-filled air next to a coal power station, Black communities have been mercilessly attacked from the outside-in: initially from smoke particulates, recently from COVID-19[10]. Similar scenes play out every day in the back gardens and living rooms of the exploited and the marginalised, ceaselessly trapping them in the gyres and currents of society’s plumes.

This show must end

From the history of rapidly industrialising nations making uneven contributions to climate change, to the effects of climate change effecting marginalised communities most acutely, to fossil fuel emissions fuelling increased susceptibility to COVID-19 in black communities, it is clear to see how inequality exacerbates, perpetuates, and reinforces each crisis. Trapped in the middle of the 3 crises, escape must feel impossible.

And yet, freedom must be delivered. This show must end. And the only way that this can happen is if we work together to tackle the central causes of these issues.

Collectively, we have a moral responsibility to develop a sustainable future – one that actively combats inequality, and that centres the plight of those that are typically left out of the spotlight.

Change is possible – there can be a different a story. And through the new perspective that COVID has given us, opportunities for recovery and improvement have started to become clear.

A different kind of story

Act 1: A Healing Environment

Through this pandemic, we have been seeing some positive – though potentially momentary –changes for the environment. There has been a decrease in global greenhouse emissions of around 5%, there has been stories of wildlife returning to cities, and the reduced noise pollution has meant that people have been able to hear the birds sing for the first time in a long time. In this period, people have begun to reconnect with nature and realise its beauty. We must continue to use this newfound knowledge and experience to help protect the environment going forward.

Act 2: Learning to protect the marginalised

The pandemic has taught us that in order to reduce the risk to marginal communities, we must embed sustainable social practices at the heart of our businesses and everyday activities. This is already being done in some communities, with people delivering groceries to those that can’t shop for themselves, by preparing meals for those working on the NHS frontline, or by spending any free time sewing facemasks and protective clothing for the vulnerable. This pandemic has given proof to the power of community spirit, we just need to keep it alive.

Act 3: Clean air to breath

This pandemic has also represented a massive pause in day-to-day life, with fewer people commuting to work and decreasing energy demands. This has meant that we have seen dramatic decreases in the levels of air pollution in cities across the world, and there has been a rapid decline in the use of fossil fuels, finally giving people the clean air that they need in order to breathe.

Our Future

Through this article, we have encountered the some of the worst effects that inequality and the COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated; but we have also encountered moments of hope. We have seen – through the lessons that this pandemic has taught – the value of nature, the strength and power of our interconnectedness, and the amazing effects that taking a pause can have.

We have also seen the damage that a crisis can bring. From this, we need to learn. We need to ensure that we are doing all that we can now to prevent the worst effects of the climate crisis – for, as we have seen, when intersecting with other crises, the climate crisis will act as the great multiplier rather than the great equaliser.

We should allow this to inspire us, and work hard to ensure that we are creating a world in which everyone has the space and clean air to breathe.

[1] Jones, O., (2020). We’re about to learn a terrible lesson from coronavirus: inequality kills https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/14/coronavirus-outbreak-inequality-austerity-pandemic

[2] Segalov, M., (2020) Interview with Emily Atkins ‘The parallels between coronavirus and climate crisis are obvious’ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/may/04/parallels-climate-coronavirus-obvious-emily-atkin-pandemic

[3] Thompson, E.P., (1963). The Making of the English Working Class. Cited in Lewis, S.L., and Maslin, M.A., (2018). The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene. Penguin Random House UK (p.190)

[4] http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/abolition/industrialisation_article_01.shtml

[5] Yusoff, K., (2018). A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. The University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis (p.66)

[6] A good introduction to the debate surrounding the Anthropocene is ‘The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene’ by Simon L. Lewis and Mark A. Maslin.

[7] E.g. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_wg3_ar5_technical-summary.pdf (p.44)

[8] IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y .O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P .R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA (p.6)

[9] Mary Robinson recounts the horrific experience of East Biloxi residents, in particular Sharon Hanshaw, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in her book ‘Climate Justice: A Man-Made Problem with a Feminist Solution’ (2019)

[10] This podcast hosted by Emily Atkins, interviewing Anthony Rogers-Wright, perfectly highlights the plight of Black communities with the onset of COIVD https://heated.world/p/episode-3-covid-19-and-climate-justice

[11] When compared to direct emissions from combined cycle gas turbines

Our Planet is in turmoil and we are helpless to do anything about it.

LikeLike